This long-term documentary project illuminates centuries of Indigenous enslavement in the American Southwest perpetrated by Spanish and Mexican colonists, as well as Mormon settlers. Through portraits of living descendants, landscapes of historical sites, and documentation of cultural performances, La Cautiva uncovers a hidden narrative of captivity and survival. Working in close collaboration with Indigenous communities, the project aims to bring forward this overlooked chapter of American history while celebrating cultural resilience and continuity. By weaving together contemporary photographs with historical research, La Cautiva creates a visual dialogue about the lasting impacts of colonialism and the importance of confronting difficult histories.

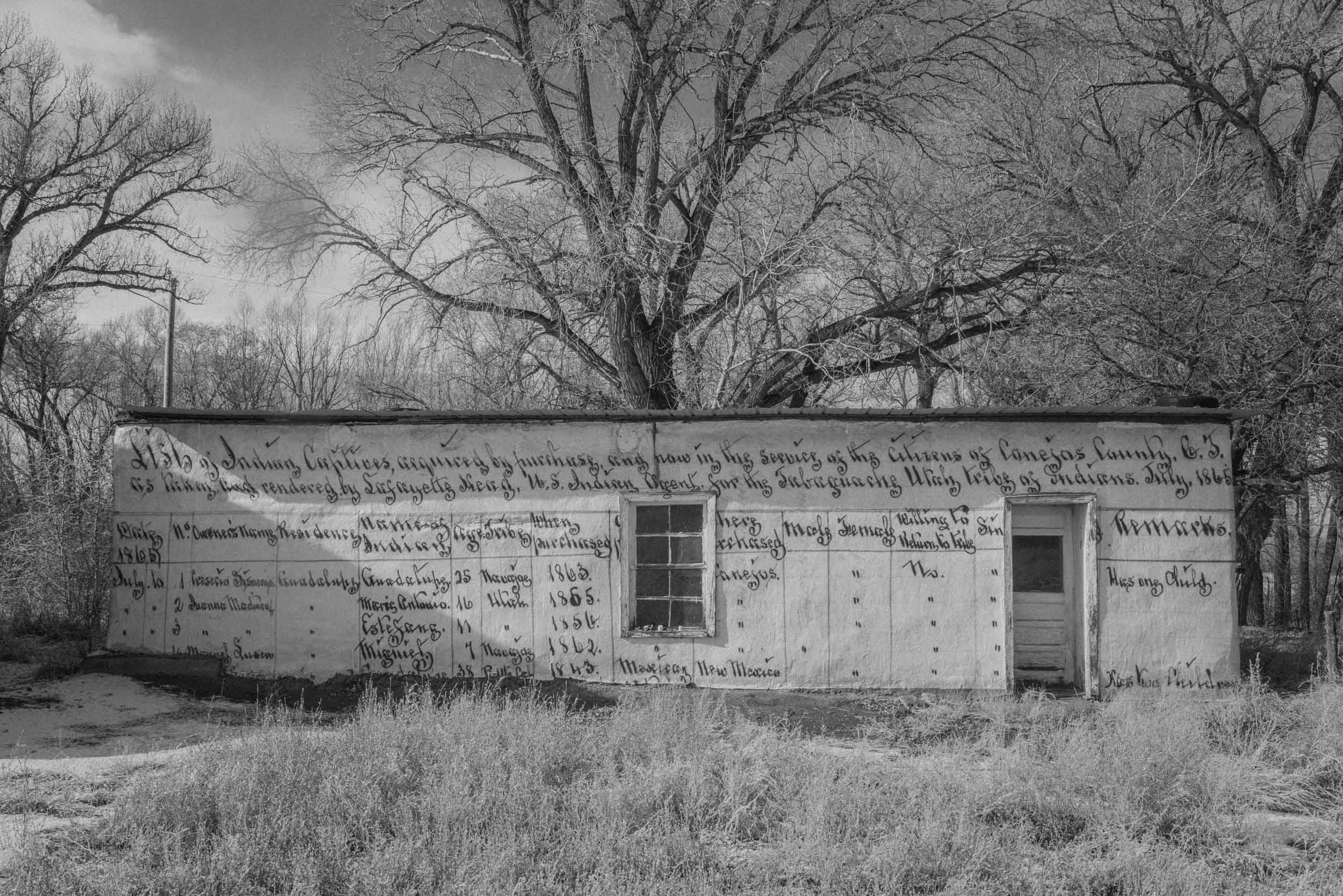

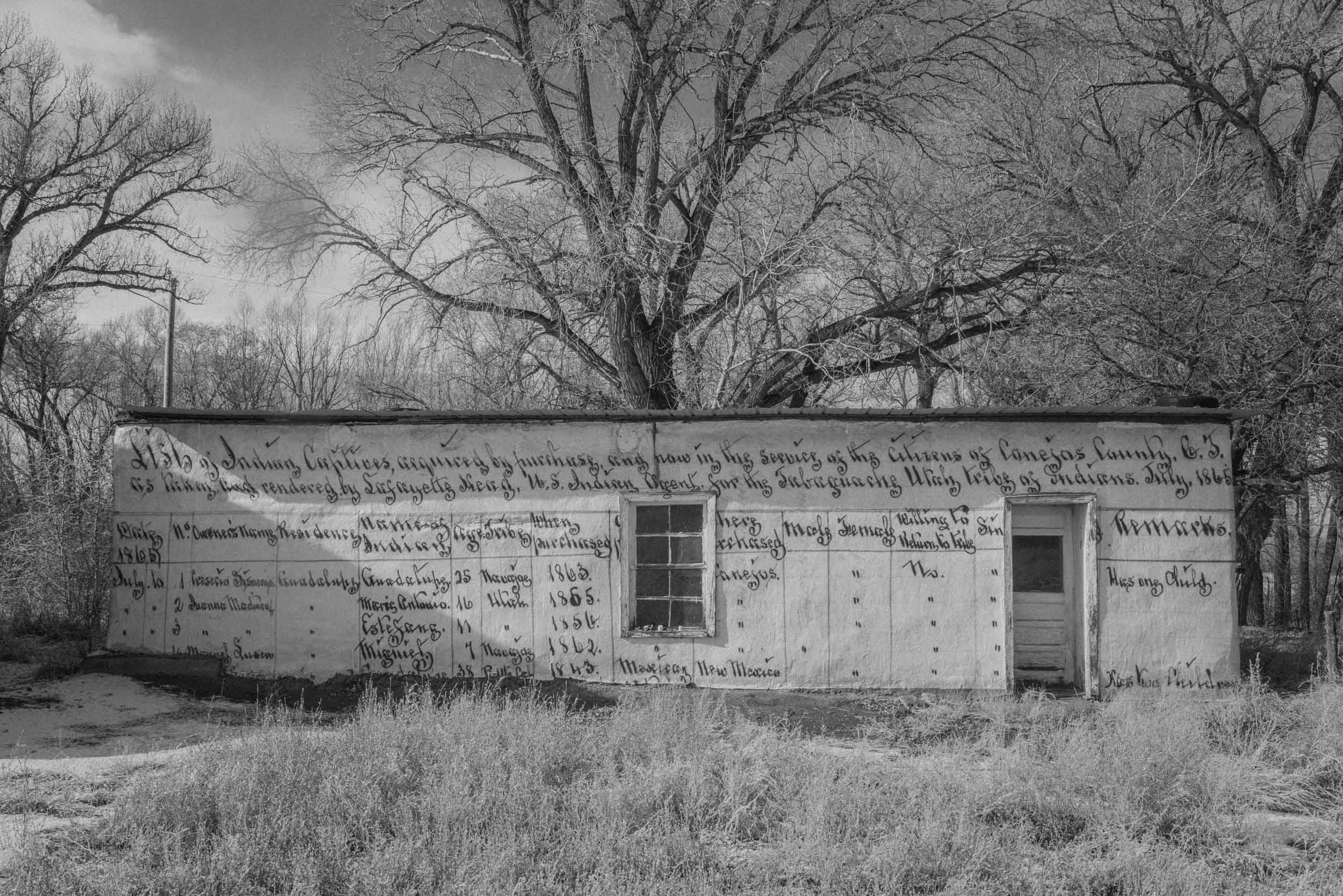

After 1492, prolonged conflicts between European colonizers and Indigenous peoples across the Western Hemisphere enabled widespread slave raiding against Native populations. By the 1600s, Spanish colonists in the Southwest had established a system of enslaving Indigenous captives taken during wars and raids. This primarily targeted members of tribes like the Hopi, Comanche, Pueblo, Apache, Ute, Pawnee, and Navajo. Over generations, this practice became entrenched in the region.

Abiquiú’s Santo Tomás feast day ceremony culminates on Sunday with El Cautivo (The Captive) Dance, which has been performed at the pueblo for more than 150 years. Dancers dress as their ancestors, with face paint, feather hair ornaments, and ankle bells. They also wear dollar bills pinned to their ceremonial clothing, signifying their “ransom”—being purchased by the Spanish from other tribes—and the beginning of their enforced servitude. Spanish law allowed them to be free after 10 to 15 years.

Ransomed by the ruling caste, they Indigenous war captives became enslaved domestic laborers, miners, field workers and odalisques. By the 1700s one third of the population of Nuevo México were free but landless Genízaro – a unique Native American and Hispanic ethnicity born from enslavement. Eventually, their existence prompted the Spanish Crown to create land grant settlements for these marginalized communities. Placed strategically along high-mountain corridors, these communities served as a militarized buffer zone against raiding tribes and to protect the colonial villas and Pueblo communities along the Rio Grande. Some of these land grant communities remain.

In 2024, the Tacoma Art Museum will host work from La Cautiva in an exhibition entitled The Abiquenos and The Artist. 12 images from the project will work in conversation with original Georgia O’Keeffe paintings to demonstrate the art historical legacy of northern New Mexico. The show, curated by Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), the first Indigenous curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

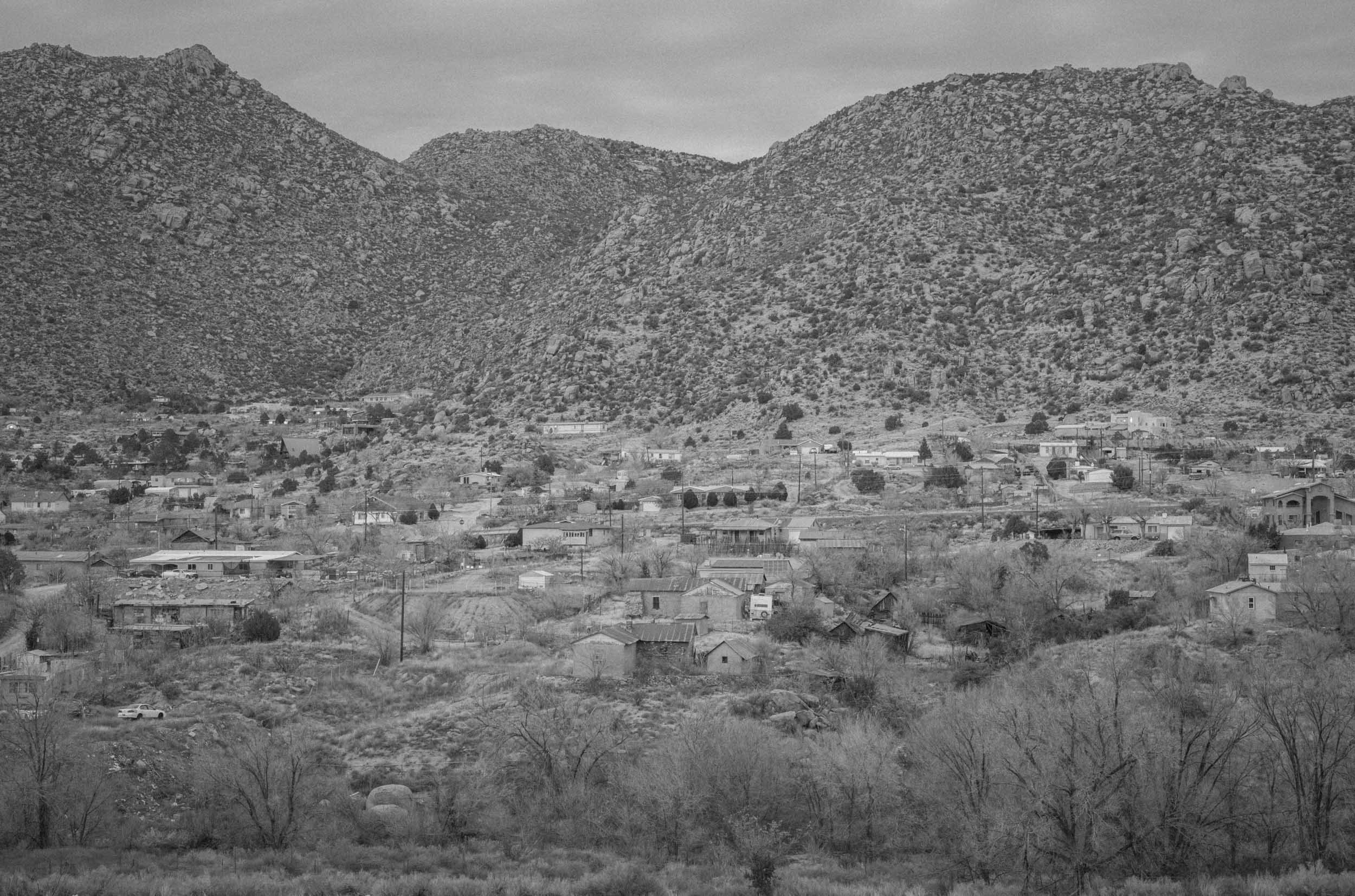

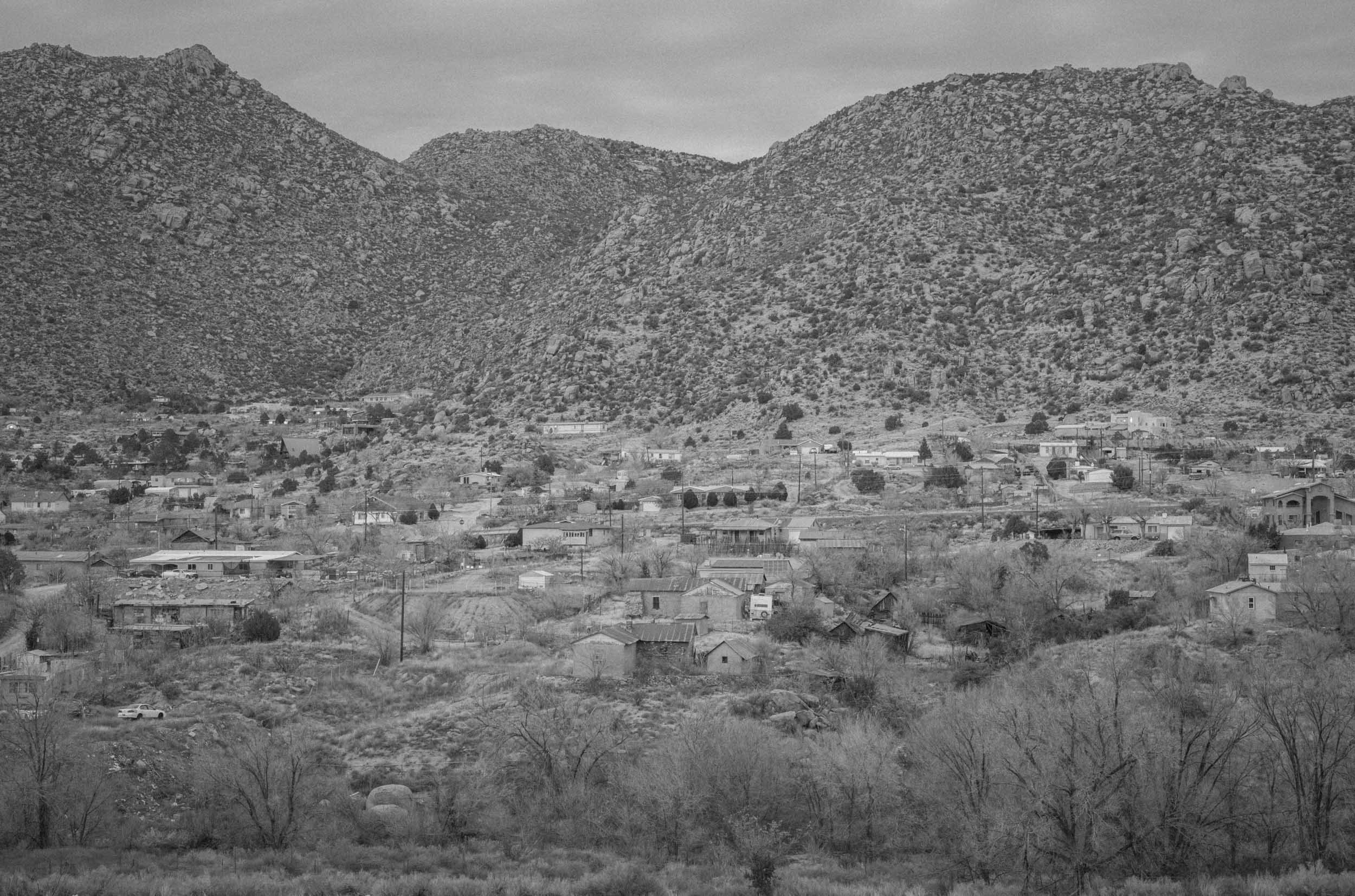

Cañón de Carnué, NM

This long-term documentary project illuminates centuries of Indigenous enslavement in the American Southwest perpetrated by Spanish and Mexican colonists, as well as Mormon settlers. Through portraits of living descendants, landscapes of historical sites, and documentation of cultural performances, La Cautiva uncovers a hidden narrative of captivity and survival. Working in close collaboration with Indigenous communities, the project aims to bring forward this overlooked chapter of American history while celebrating cultural resilience and continuity. By weaving together contemporary photographs with historical research, La Cautiva creates a visual dialogue about the lasting impacts of colonialism and the importance of confronting difficult histories.

After 1492, prolonged conflicts between European colonizers and Indigenous peoples across the Western Hemisphere enabled widespread slave raiding against Native populations. By the 1600s, Spanish colonists in the Southwest had established a system of enslaving Indigenous captives taken during wars and raids. This primarily targeted members of tribes like the Hopi, Comanche, Pueblo, Apache, Ute, Pawnee, and Navajo. Over generations, this practice became entrenched in the region.

Abiquiú’s Santo Tomás feast day ceremony culminates on Sunday with El Cautivo (The Captive) Dance, which has been performed at the pueblo for more than 150 years. Dancers dress as their ancestors, with face paint, feather hair ornaments, and ankle bells. They also wear dollar bills pinned to their ceremonial clothing, signifying their “ransom”—being purchased by the Spanish from other tribes—and the beginning of their enforced servitude. Spanish law allowed them to be free after 10 to 15 years.

Ransomed by the ruling caste, they Indigenous war captives became enslaved domestic laborers, miners, field workers and odalisques. By the 1700s one third of the population of Nuevo México were free but landless Genízaro – a unique Native American and Hispanic ethnicity born from enslavement. Eventually, their existence prompted the Spanish Crown to create land grant settlements for these marginalized communities. Placed strategically along high-mountain corridors, these communities served as a militarized buffer zone against raiding tribes and to protect the colonial villas and Pueblo communities along the Rio Grande. Some of these land grant communities remain.

In 2024, the Tacoma Art Museum will host work from La Cautiva in an exhibition entitled The Abiquenos and The Artist. 12 images from the project will work in conversation with original Georgia O’Keeffe paintings to demonstrate the art historical legacy of northern New Mexico. The show, curated by Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), the first Indigenous curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Cañón de Carnué, NM